Weight Control

Aerodynamics of Flight, weight is the force with which gravity attracts a body toward the center of the Earth. It is a product of the mass of a body and the acceleration acting on the body. Weight is a major factor in aircraft construction and operation, and demands respect from all pilots.

The force of gravity continuously attempts to pull an aircraft down toward Earth. The force of lift is the only force that counteracts weight and sustains an aircraft in flight. The amount of lift produced by an airfoil is limited by the airfoil design, angle of attack (AOA), airspeed, and air density. To assure that the lift generated is sufficient to counteract weight, loading an aircraft beyond the manufacturer’s recommended weight must be avoided. If the weight is greater than the lift generated, the aircraft may be incapable of flight.

Effects of Weight

Any item aboard the aircraft that increases the total weight is undesirable for performance. Manufacturers attempt to make an aircraft as light as possible without sacrificing strength or safety.

The pilot should always be aware of the consequences of overloading. An overloaded aircraft may not be able to leave the ground, or if it does become airborne, it may exhibit unexpected and unusually poor flight characteristics. If not properly loaded, the initial indication of poor performance usually takes place during takeoff.

Excessive weight reduces the flight performance in almost every respect. For example, the most important performance deficiencies of an overloaded aircraft are:

- Higher takeoff speed

- Longer takeoff run

- Reduced rate and angle of climb

- Lower maximum altitude

- Shorter range

- Reduced cruising speed

- Reduced maneuverability

- Higher stalling speed

- Higher approach and landing speed

- Longer landing roll

- Excessive weight on the nose wheel or tail wheel

Weight Changes The operating weight of an aircraft can be changed by simply altering the fuel load. Gasoline has considerable weight—6 pounds per gallon. Thirty gallons of fuel may weigh more than one passenger. If a pilot lowers airplane weight by reducing fuel, the resulting decrease in the range of the airplane must be taken into consideration during flight planning. During flight, fuel burn is normally the only weight change that takes place. As fuel is used, an aircraft becomes lighter and performance is improved.

Changes of fixed equipment have a major effect upon the weight of an aircraft. The installation of extra radios or instruments, as well as repairs or modifications may also affect the weight of an aircraft.

Balance, Stability, and Center of Gravity

Balance refers to the location of the CG of an aircraft, and is important to stability and safety in flight. The CG is a point at which the aircraft would balance if it were suspended at that point.

The primary concern in balancing an aircraft is the fore and aft location of the CG along the longitudinal axis. The CG is not necessarily a fixed point; its location depends on the distribution of weight in the aircraft. As variable load items are shifted or expended, there is a resultant shift in CG location. The distance between the forward and back limits for the position of the center for gravity or CG range is certified for an aircraft by the manufacturer. The pilot should realize that if the CG is displaced too far forward on the longitudinal axis, a nose-heavy condition will result. Conversely, if the CG is displaced too far aft on the longitudinal axis, a tail heavy condition results. It is possible that the pilot could not control the aircraft if the CG location produced an unstable condition.

[Figure 9-1]

Figure 9-1. Lateral and longitudinal unbalance.

Location of the CG with reference to the lateral axis is also important. For each item of weight existing to the left of the fuselage centerline, there is an equal weight existing at a corresponding location on the right. This may be upset by unbalanced lateral loading. The position of the lateral CG is not computed in all aircraft, but the pilot must be aware that adverse effects arise as a result of a laterally unbalanced condition. In an airplane, lateral unbalance occurs if the fuel load is mismanaged by supplying the engine(s) unevenly from tanks on one side of the airplane. The pilot can compensate for the resulting wing-heavy condition by adjusting the trim or by holding a constant control pressure. This action places the aircraft controls in an out-of-streamline condition, increases drag, and results in decreased operating efficiency. Since lateral balance is addressed when needed in the aircraft flight manual (AFM) and longitudinal balance is more critical, further reference to balance in this handbook means longitudinal location of the CG. A single pilot operating a small rotorcraft, may require additional weight to keep the aircraft laterally balanced.

Flying an aircraft that is out of balance can produce increased pilot fatigue with obvious effects on the safety and efficiency of flight. The pilot’s natural correction for longitudinal unbalance is a change of trim to remove the excessive control pressure. Excessive trim, however, has the effect of reducing not only aerodynamic efficiency but also primary control travel distance in the direction the trim is applied.

Effects of Adverse Balance

Adverse balance conditions affect flight characteristics in much the same manner as those mentioned for an excess weight condition. It is vital to comply with weight and balance limits established for all aircraft, especially rotorcraft. Operating above the maximum weight limitation compromises the structural integrity of the rotorcraft and adversely affects performance. Balance is also critical because on some fully loaded rotorcraft, CG deviations as small as three inches can dramatically change handling characteristics. Stability and control are also affected by improper balance.

Stability

Loading in a nose-heavy condition causes problems in controlling and raising the nose, especially during takeoff and landing. Loading in a tail heavy condition has a serious effect upon longitudinal stability, and reduces the capability to recover from stalls and spins. Tail heavy loading also produces very light control forces, another undesirable characteristic. This makes it easy for the pilot to inadvertently overstress an aircraft.

It is important to reevaluate the balance in a rotorcraft whenever loading changes. In most aircraft, off-loading a passenger is unlikely to adversely affect the CG, but offloading a passenger from a rotorcraft can create an unsafe flight condition. An out-of-balance loading condition also decreases maneuverability since cyclic control is less effective in the direction opposite to the CG location.

Limits for the location of the CG are established by the manufacturer. These are the fore and aft limits beyond which the CG should not be located for flight. These limits are published for each aircraft in the Type Certificate Data Sheet (TCDS), or aircraft specification and the AFM or pilot’s operating handbook (POH). If the CG is not within the allowable limits after loading, it will be necessary to relocate some items before flight is attempted.

The forward CG limit is often established at a location that is determined by the landing characteristics of an aircraft. During landing, one of the most critical phases of flight, exceeding the forward CG limit may result in excessive loads on the nosewheel, a tendency to nose over on tailwheel type airplanes, decreased performance, higher stalling speeds, and higher control forces.

Control

In extreme cases, a CG location that is beyond the forward limit may result in nose heaviness, making it difficult or impossible to flare for landing. Manufacturers purposely place the forward CG limit as far rearward as possible to aid pilots in avoiding damage when landing. In addition to decreased static and dynamic longitudinal stability, other undesirable effects caused by a CG location aft of the allowable range may include extreme control difficulty, violent stall characteristics, and very light control forces which make it easy to overstress an aircraft inadvertently.

A restricted forward CG limit is also specified to assure that sufficient elevator/control deflection is available at minimum airspeed. When structural limitations do not limit the forward CG position, it is located at the position where full-up elevator/control deflection is required to obtain a high AOA for landing.

The aft CG limit is the most rearward position at which the CG can be located for the most critical maneuver or operation. As the CG moves aft, a less stable condition occurs, which decreases the ability of the aircraft to right itself after maneuvering or turbulence.

For some aircraft, both fore and aft CG limits may be specified to vary as gross weight changes. They may also be changed for certain operations, such as acrobatic flight, retraction of the landing gear, or the installation of special loads and devices that change the flight characteristics.

The actual location of the CG can be altered by many variable factors and is usually controlled by the pilot. Placement of baggage and cargo items determines the CG location. The assignment of seats to passengers can also be used as a means of obtaining a favorable balance. If an aircraft is tail heavy, it is only logical to place heavy passengers in forward seats.

Fuel burn can also affect the CG based on the location of the fuel tanks. For example, most small aircraft carry fuel in the wings very near the CG and burning off fuel has little effect on the loaded CG. On rotorcraft, the fuel tanks are often located behind the CG and fuel consumption from a tank aft of the rotor mast causes the loaded CG to move forward. A rotorcraft in this condition has a nose-low attitude when coming to a hover following a vertical takeoff. Excessive rearward displacement of the cyclic control is needed to maintain a hover in a no-wind condition. Flight should not be continued since rearward cyclic control fades as fuel is consumed. Deceleration to a stop may also be impossible. In the event of engine failure and autorotation, there may not be enough cyclic control to flare properly for a landing.

Management of Weight and Balance

Control Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) section 23.23 requires establishment of the ranges of weights and CGs within which an aircraft may be operated safely. The manufacturer provides this information, which is included in the approved AFM, TCDS, or aircraft specifications.

While there are no specified requirements for a pilot operating under 14 CFR part 91 to conduct weight and balance calculations prior to each flight, 14 CFR section 91.9 requires the pilot in command (PIC) to comply with the operating limits in the approved AFM. These limits include the weight and balance of the aircraft. To enable pilots to make weight and balance computations, charts and graphs are provided in the approved AFM.

Weight and balance control should be a matter of concern to all pilots. The pilot controls loading and fuel management (the two variable factors that can change both total weight and CG location) of a particular aircraft. The aircraft owner or operator should make certain that up-to-date information is available for pilot use, and should ensure that appropriate entries are made in the records when repairs or modifications have been accomplished. The removal or addition of equipment results in changes to the CG.

Weight changes must be accounted for and the proper notations made in weight and balance records. The equipment list must be updated, if appropriate. Without such information, the pilot has no foundation upon which to base the necessary calculations and decisions.

Standard parts with negligible weight or the addition of minor items of equipment such as nuts, bolts, washers, rivets, and similar standard parts of negligible weight on fixed-wing aircraft do not require a weight and balance check. Rotorcraft are, in general, more critical with respect to control with changes in the CG position. The following criteria for negligible weight change is outlined in Advisory Circular (AC) 43.13-1 (as revised), Methods Techniques and Practices—Aircraft Inspection and Repair:

- One pound or less for an aircraft whose weight empty is less than 5,000 pounds;

- Two pounds or less for aircraft with an empty weight of more than 5,000 pounds to 50,000 pounds;

- Five pounds or less for aircraft with an empty weight of more than 50,000 pounds.

Before any flight, the pilot should determine the weight and balance condition of the aircraft. Simple and orderly procedures based on sound principles have been devised by the manufacturer for the determination of loading conditions. The pilot uses these procedures and exercises good judgment when determining weight and balance. In many modern aircraft, it is not possible to fill all seats, baggage compartments, and fuel tanks, and still remain within the approved weight and balance limits. If the maximum passenger load is carried, the pilot must often reduce the fuel load or reduce the amount of baggage.

14 CFR part 125 requires aircraft with 20 or more seats or weighing 6,000 pounds or more to be weighed every 36 calendar months. Multi-engine aircraft operated under a 14 CFR part 135 are also required to be weighed every 36 months. Aircraft operated under 14 CFR part 135 are exempt from the 36 month requirement if operated under a weight and balance system approved in the operations specifications of the certificate holder. AC 43.13-1, Acceptable Methods, Techniques and Practices—Aircraft Inspection and Repair also requires that the aircraft mechanic must ensure the weight and balance data in the aircraft records is current and accurate after a 100-hour or annual inspection.

Terms and Definitions

The pilot should be familiar with terms used in working problems related to weight and balance. The following list of terms and their definitions is standardized, and knowledge of these terms aids the pilot to better understand weight and balance calculations of any aircraft. Terms defined by the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA) as industry standard are marked in the titles with GAMA.

Arm (moment arm)—the horizontal distance in inches from the reference datum line to the CG of an item. The algebraic sign is plus (+) if measured aft of the datum, and minus (–) if measured forward of the datum.

- Basic empty weight (GAMA)—the standard empty weight plus the weight of optional and special equipment that have been installed.

- Center of gravity (CG)—the point about which an aircraft would balance if it were possible to suspend it at that point. It is the mass center of the aircraft, or the theoretical point at which the entire weight of the aircraft is assumed to be concentrated. It may be expressed in inches from the reference datum, or in percent of MAC. The CG is a three-dimensional point with longitudinal, lateral, and vertical positioning in the aircraft.

- CG limits—the specified forward and aft points within which the CG must be located during flight. These limits are indicated on pertinent aircraft specifications.

- CG range—the distance between the forward and aft CG limits indicated on pertinent aircraft specifications. • Datum (reference datum)—an imaginary vertical plane or line from which all measurements of arm are taken. The datum is established by the manufacturer. Once the datum has been selected, all moment arms and the location of CG range are measured from this point.

- Delta—a Greek letter expressed by the symbol △ to indicate a change of values. As an example, △CG indicates a change (or movement) of the CG.

- Floor load limit—the maximum weight the floor can sustain per square inch/foot as provided by the manufacturer.

- Fuel load—the expendable part of the load of the aircraft. It includes only usable fuel, not fuel required to fill the lines or that which remains trapped in the tank sumps.

- Licensed empty weight—the empty weight that consists of the airframe, engine(s), unusable fuel, and undrainable oil plus standard and optional equipment as specified in the equipment list. Some manufacturers used this term prior to GAMA standardization.

- Maximum landing weight—the greatest weight that an aircraft normally is allowed to have at landing.

- Maximum ramp weight—the total weight of a loaded aircraft, and includes all fuel. It is greater than the takeoff weight due to the fuel that will be burned during the taxi and runup operations. Ramp weight may also be referred to as taxi weight.Maximum takeoff weight—the maximum allowable weight for takeoff.

- Maximum weight—the maximum authorized weight of the aircraft and all of its equipment as specified in the TCDS for the aircraft.

- Maximum zero fuel weight (GAMA)—the maximum weight, exclusive of usable fuel.

- Mean aerodynamic chord (MAC)—the average distance from the leading edge to the trailing edge of the wing.

- Moment—the product of the weight of an item multiplied by its arm. Moments are expressed in pound-inches (in-lb). Total moment is the weight of the airplane multiplied by the distance between the datum and the CG.

- Moment index (or index)—a moment divided by a constant such as 100, 1,000, or 10,000. The purpose of using a moment index is to simplify weight and balance computations of aircraft where heavy items and long arms result in large, unmanageable numbers.

- Payload (GAMA)—the weight of occupants, cargo, and baggage.

- Standard empty weight (GAMA)—aircraft weight that consists of the airframe, engines, and all items of operating equipment that have fixed locations and are permanently installed in the aircraft, including fixed ballast, hydraulic fluid, unusable fuel, and full engine oil.

- Standard weights—established weights for numerous items involved in weight and balance computations. These weights should not be used if actual weights are available. Some of the standard weights are:

- Gasoline ............................................... 6 lb/US gal

- Jet A, Jet A-1 .................................... 6.8 lb/US gal

- Jet B ...................................................6.5 lb/US gal

- Oil ......................................................7.5 lb/US gal

- Water .....................................................8.35 lb/US gal

- Station—a location in the aircraft that is identified by a number designating its distance in inches from the datum. The datum is, therefore, identified as station zero. An item located at station +50 would have an arm of 50 inches.

- Useful load—the weight of the pilot, copilot, passengers, baggage, usable fuel, and drainable oil. It is the basic empty weight subtracted from the maximum allowable gross weight. This term applies to general aviation (GA) aircraft only.

It might be advantageous at this point to review and discuss some of the basic principles of weight and balance determination. The following method of computation can be applied to any object or vehicle for which weight and balance information is essential.

By determining the weight of the empty aircraft and adding the weight of everything loaded on the aircraft, a total weight can be determined—a simple concept. A greater problem, particularly if the basic principles of weight and balance are not understood, is distributing this weight in such a manner that the entire mass of the loaded aircraft is balanced around a point (CG) that must be located within specified limits.

The point at which an aircraft balances can be determined by locating the CG, which is, as stated in the definitions of terms, the imaginary point at which all the weight is concentrated. To provide the necessary balance between longitudinal stability and elevator control, the CG is usually located slightly forward of the center of lift. This loading condition causes a nose-down tendency in flight, which is desirable during flight at a high AOA and slow speeds.

As mentioned earlier, a safe zone within which the balance point (CG) must fall is called the CG range. The extremities of the range are called the forward CG limits and aft CG limits. These limits are usually specified in inches, along the longitudinal axis of the airplane, measured from a reference point called a datum reference. The datum is an arbitrary point, established by aircraft designers, which may vary in location between different aircraft. [Figure 9-2]

Figure 9-2. Weight and balance.

The distance from the datum to any component part or any object loaded on the aircraft, is called the arm. When the object or component is located aft of the datum, it is measured in positive inches; if located forward of the datum, it is measured as negative inches, or minus inches. The location of the object or part is often referred to as the station. If the weight of any object or component is multiplied by the distance from the datum (arm), the product is the moment. The moment is the measurement of the gravitational force that causes a tendency of the weight to rotate about a point or axis and is expressed in inch-pounds (in-lb).

To illustrate, assume a weight of 50 pounds is placed on the board at a station or point 100 inches from the datum. The downward force of the weight can be determined by multiplying 50 pounds by 100 inches, which produces a moment of 5,000 in-lb. [Figure 9-3]

Figure 9-3. Determining moment.

To establish a balance, a total of 5,000 in-lb must be applied to the other end of the board. Any combination of weight and distance which, when multiplied, produces a 5,000 in-lb moment will balance the board. For example (illustrated in Figure 9-4), if a 100-pound weight is placed at a point (station) 25 inches from the datum, and another 50-pound weight is placed at a point (station) 50 inches from the datum, the sum of the product of the two weights and their distances will total a moment of 5,000 in-lb, which will balance the board.

Figure 9-4. Establishing a balance.

Weight and Balance Restrictions

An aircraft’s weight and balance restrictions should be closely followed. The loading conditions and empty weight of a particular aircraft may differ from that found in the AFM/POH because modifications or equipment changes may have been made. Sample loading problems in the AFM/POH are intended for guidance only; therefore, each aircraft must be treated separately. Although an aircraft is certified for a specified maximum gross takeoff weight, it will not safely take off with this load under all conditions. Conditions that affect takeoff and climb performance, such as high elevations, high temperatures, and high humidity (high density altitudes) may require a reduction in weight before flight is attempted. Other factors to consider prior to takeoff are runway length, runway surface, runway slope, surface wind, and the presence of obstacles. These factors may require a reduction in weight prior to flight.

Some aircraft are designed so that it is difficult to load them in a manner that will place the CG out of limits. These are usually small aircraft with the seats, fuel, and baggage areas located near the CG limit. Pilots must be aware that while within CG limits these aircraft can be overloaded in weight. Other aircraft can be loaded in such a manner that they will be out of CG limits even though the useful load has not been exceeded. Because of the effects of an out-of-balance or overweight condition, a pilot should always be sure that an aircraft is properly loaded.

Determining Loaded Weight and CG

There are various methods for determining the loaded weight and CG of an aircraft. There is the computational method, as well as methods that utilize graphs and tables provided by the aircraft manufacturer.

Computational Method

The following is an example of the computational method involving the application of basic math functions.

- Aircraft Allowances:

Maximum gross weight.................................... 3,400 pounds

CG range.......................................................... 78–86 inches

- Given:

Weight of front seat occupants................. 340 pounds

Weight of rear seat occupants................... 350 pounds

Fuel........................................................... 75 gallons

Weight of baggage in area 1..................... 80 pounds

- List the weight of the aircraft, occupants, fuel, and baggage. Remember that aviation gas (AVGAS) weighs 6 pounds per gallon and is used in this example.

- Enter the moment for each item listed. Remember “weight x arm = moment.”

- Find the total weight and total moment.

- To determine the CG, divide the total moment by the total weight.

NOTE: The weight and balance records for a particular aircraft will provide the empty weight and moment, as well as the information on the arm distance. [Figure 9-5]

Figure 9-5. Example of weight and balance computations.

The total loaded weight of 3,320 pounds does not exceed the maximum gross weight of 3,400 pounds, and the CG of 84.8 is within the 78–86 inch range; therefore, the aircraft is loaded within limits.

Graph Method

Another method for determining the loaded weight and CG is the use of graphs provided by the manufacturers. To simplify calculations, the moment may sometimes be divided by 100, 1,000, or 10,000. [Figures 9-6, 9-7, and 9-8]

Front seat occupants..........................................340 pounds

Rear seat occupants ..........................................300 pounds

Fuel .................................................................40 gallons

Baggage area 1 ................................................20 pounds

Figure 9-6. Weight and balance data.

Figure 9-7. Loading graph.

Figure 9-8. CG moment envelope.

The same steps should be followed as in the computational method except the graphs provided will calculate the moments and allow the pilot to determine if the aircraft is loaded within limits. To determine the moment using the loading graph, find the weight and draw a line straight across until it intercepts the item for which the moment is to be calculated. Then draw a line straight down to determine the moment. (The red line on the loading graph represents the moment for the pilot and front passenger. All other moments were determined in the same way.) Once this has been done for each item, total the weight and moments and draw a line for both weight and moment on the CG envelope graph. If the lines intersect within the envelope, the aircraft is loaded within limits. In this sample loading problem, the aircraft is loaded within limits.

Table Method

The table method applies the same principles as the computational and graph methods. The information and limitations are contained in tables provided by the manufacturer. Figure 9-9 is an example of a table and a weight and balance calculation based on that table. In this problem, the total weight of 2,799 pounds and moment of 2,278/100 are within the limits of the table.

Figure 9-9. Loading schedule placard.

Computations With a Negative Arm

Figure 9-10 is a sample of weight and balance computation using an airplane with a negative arm. It is important to remember that a positive times a negative equals a negative, and a negative would be subtracted from the total moments.

Figure 9-10. Sample weight and balance using a negative.

Computations With Zero Fuel Weight

Figure 9-11 is a sample of weight and balance computation using an aircraft with a zero fuel weight. In this example, the total weight of the aircraft less fuel is 4,240 pounds, which is under the zero fuel weight of 4,400 pounds. If the total weight of the aircraft without fuel had exceeded 4,400 pounds, passengers or cargo would have needed to be reduced to bring the weight at or below the max zero fuel weight.

Figure 9-11. Sample weight and balance using an aircraft with a published zero fuel weight.

Shifting, Adding, and Removing Weight

A pilot must be able to solve any problems accurately that involve the shift, addition, or removal of weight. For example, the pilot may load the aircraft within the allowable takeoff weight limit, then find a CG limit has been exceeded. The most satisfactory solution to this problem is to shift baggage, passengers, or both. The pilot should be able to determine the minimum load shift needed to make the aircraft safe for flight. Pilots should be able to determine if shifting a load to a new location will correct an out-of-limit condition. There are some standardized calculations that can help make these determinations.

Weight Shifting

When weight is shifted from one location to another, the total weight of the aircraft is unchanged. The total moments, however, do change in relation and proportion to the direction and distance the weight is moved. When weight is moved forward, the total moments decrease; when weight is moved aft, total moments increase. The moment change is proportional to the amount of weight moved. Since many aircraft have forward and aft baggage compartments, weight may be shifted from one to the other to change the CG. If starting with a known aircraft weight, CG, and total moments, calculate the new CG (after the weight shift) by dividing the new total moments by the total aircraft weight.

To determine the new total moments, find out how many moments are gained or lost when the weight is shifted. Assume that 100 pounds has been shifted from station 30 to station 150. This movement increases the total moments of the aircraft by 12,000 in-lb.

Moment when at station 150 = 100 lb x 150 in = 15,000 in-lb

Moment when at station 30 = 100 lb x 30 in = 3,000 in-lb

Moment change = [15,000 - 3,000] = 12,000 in-lb

Moment when at station 30 = 100 lb x 30 in = 3,000 in-lb

Moment change = [15,000 - 3,000] = 12,000 in-lb

By adding the moment change to the original moment (or subtracting if the weight has been moved forward instead of aft), the new total moments are obtained. Then determine the new CG by dividing the new moments by the total weight:

Total moments = 616,000 in-lb + 12,000 in-lb = 628,000 in-lb

CG = 628,000 in-lb = 78.5 in

8,000 lb

The shift has caused the CG to shift to station 78.5.

The shift has caused the CG to shift to station 78.5.

A simpler solution may be obtained by using a computer or calculator and a proportional formula. This can be done because the CG will shift a distance that is proportional to the distance the weight is shifted.

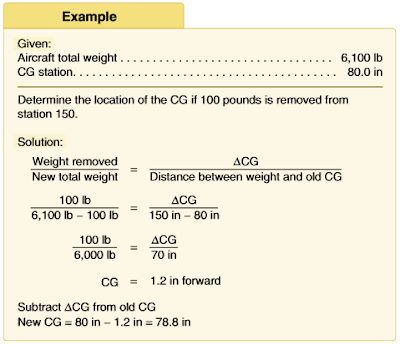

Weight Addition or Removal

In many instances, the weight and balance of the aircraft will be changed by the addition or removal of weight. When this happens, a new CG must be calculated and checked against the limitations to see if the location is acceptable. This type of weight and balance problem is commonly encountered

when the aircraft burns fuel in flight, thereby reducing the weight located at the fuel tanks. Most small aircraft are designed with the fuel tanks positioned close to the CG; therefore, the consumption of fuel does not affect the CG to any great extent.

The addition or removal of cargo presents a CG change problem that must be calculated before flight. The problem may always be solved by calculations involving total moments. A typical problem may involve the calculation of a new CG for an aircraft which, when loaded and ready for flight, receives some additional cargo or passengers just before departure time.

In the previous examples, the △CG is either added or subtracted from the old CG. Deciding which to accomplish is best handled by mentally calculating which way the CG will shift for the particular weight change. If the CG is shifting aft, the △CG is added to the old CG; if the CG is shifting forward, the △CG is subtracted from the old CG.

Summary

Operating an aircraft within the weight and balance limits is critical to flight safety. Pilots must ensure that the CG is and remains within approved limits for all phases of a flight. Additional information on weight, balance, CG, and aircraft stability can be found in FAA-H-8083-1, Aircraft Weight and Balance Handbook. Those pilots flying helicopters or gyroplanes should consult the Rotorcraft Flying Handbook, FAA-H-8083-21, for specific information relating to aircraft type.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.